The Whistleblower Project

– Introduction

– A Call to Action: Whistleblower Protection Legislation

If passed, these laws would help improve protection for whistleblowers.

Whistleblower Basics

– The Law and Whistleblowing

Deciphering the laws dealing with whistleblowing is complicated, but we hope this will help.

– Whistleblowers and Retaliation

Those who expose wrongdoing can face job loss, lawsuits or even prison.

– Leaking vs. Whistleblowing

Can you spot the difference between a leaker and a whistleblower? It may be trickier than you think.

– Nine Organizations That Work With and Help Whistleblowers

Best Practices for Journalists

– Source Protection and Anonymity for Whistleblowers

In political journalism, there’s a debate over allowing sources to talk to you off the record, in order to keep the access pipeline flowing. Anonymity and the ethics of it can also be complicated in situations beyond scoring political points.

– Whistleblowers and Reporters: Trust

Here are some best practices to follow when working with a whistleblower on a story.

– Technology Can Help Whistleblowers Communicate Anonymously

The ways that reporters and whistleblowers communicate is evolving. The introduction of secure communications has become necessary as journalists try to protect their sources, all the while trying to guarantee the information is secure.

– Anonymity: Not Always the Possible, Nor Always the Best, Strategy

Many whistleblowers want to disclose information about trouble in their workplaces while maintaining their anonymity. However, the vast majority of whistleblowers — more than 95 percent — try to solve their problems internally first.

– When Working with Whistleblowers, Same Ethical Journalism Principles Apply

Government Accountability Project’s “Working with Whistleblowers: A Guide for Journalists” details best practices for working with whistleblowers.

Voices

– Kathryn Foxhall: Good whistleblowing simply needs free speech

During the last 25 years it’s become an accepted norm for government, business, nonprofits and other organizations to prohibit employees to ever communicate with journalists without notifying and being overseen by the authorities, often public information officers. The restrictions are intense, highly effective censorship. The Society of Professional Journalists has made opposing them a priority.

– Jesselyn Radack: Challenges in Defending National Security Whistleblowers

War crimes, mass surveillance, torture: some of the biggest stories in modern history relied on whistleblowers in national security and intelligence agencies. They came forward at great risk to expose the truth.

– Nick Schwellenbach: The Modern Politics of American Whistleblowing

Insiders Valued More Highly in U.S. Society, But Still Face Perils.

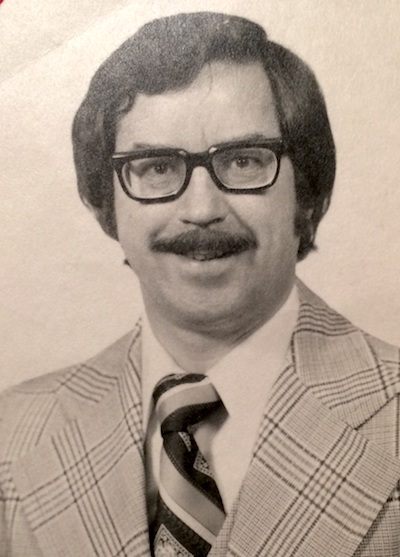

Physicist Aldric Saucier blew the whistle on gross mismanagement and waste of funds associated with the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), otherwise known as the Star Wars program.

Get the full details of Aldric's story, along with 24 other times whistleblowers changed history.

Physicist Aldric Saucier blew the whistle on gross mismanagement and waste of funds associated with the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), otherwise known as the Star Wars program.

Get the full details of Aldric's story, along with 24 other times whistleblowers changed history.

Features

– Mary Willingham: An Attempt To Make The College Athletic System Better For Athletes

Mary Willingham talks about why she spoke out about the treatment of college athletes at North Carolina and why — despite death threats from college sports enthusiasts — she would do it again.

– Megan Wood: Reporting with Purpose

Megan Wood talks about why she looked into San Diego Christian College’s missing $20 million in expenses and how whistleblowers make a difference in their communities.

– Richard Bowen: Blowing the Whistle on Defective Mortgages

While evaluating $90 billion of mortgages Citigroup was buying from Countrywide and other lenders, former Citigroup vice president Richard Bowen tried to warn company leaders and board members about the rise in defective mortgages. In 2010 he testified before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. Here, in Bowen’s words, is what happened next.

– Craig Watts: Typical American Farmer Risks Career to Reveal Inhumane Conditions at Chicken Farms

Craig Watts was a typical American farmer with three kids, two dogs, and a barn full of chickens. That all changed though when he decided to show the public the conditions chickens, sold by Perdue farms, were being raised in.

Credits

Meet the Project Team

The relationship between reporter and confidential source is sacred and contractual. As the Supreme Court described in Cohen v. Cowles Media (1991), a source provides information to the reporter in exchange for confidentiality (the reporter not revealing the source’s identity). In Cohen, reporters for two newspapers burned a source who was promised confidentiality. Cohen lost his job, sued for damages and the court held that the First Amendment could not be invoked to allow the newspapers to break the promise of confidentiality.

To further complicate this issue, the Supreme Court has also ruled that reporters have no greater right to avoid general laws than anyone else. This has played out in cases testing the existence or extent of the reporter’s privilege. The question tested in such cases is whether a reporter will have to turn over information or testify before a tribunal, often a grand jury, about the source of confidential information.

In recent years, the reporter’s privilege has been tested in leak investigations — government investigations into the source of information that was given to reporters. The intent of the investigation is to uncover the source of the information, often classified or secret information, that becomes the basis of news stories. Think Edward Snowden, Chelsea Manning or recently, Reality Winner, who disseminated classified information to reporters and subsequently paid a price.

Because reporter’s privilege standards vary from state to state and efforts to pass a federal shield law have been unsuccessful, reporters find themselves in potentially-precarious positions when dealing with confidentiality.

In some high-profile cases, reporters run the risk of revealing a source’s identity — burning the source and exposing the source to possible sanctions or other dangers — or potentially facing time in jail for contempt of court for refusing to reveal that source’s identity. The New York Times’ Judith Miller ended up spending 85 days in jail on contempt of court charges for failing to disclose the identity of a confidential source.

There is no clear formula for how reporters find whistleblowers or how they interact with them once they have come together. Reporters have an obligation to seek and report the truth. They also have an obligation to protect their sources, especially whistleblowers.

In the digital age, email and phone communications can easily be monitored. Employees have limited-to-no expectation of privacy with relation to workplace communications. Investigators might not even need to subpoena a reporter nowadays to determine a source’s identity.

Thus, the reporter must take precautions to ensure the source is obscured or protected. This almost harkens back to those famous scenes in “All the President’s Men,” where Washington Post Reporter Bob Woodward meets Deep Throat (Mark Felt) in a darkened parking deck. We might be going back to those days.

Some whistleblower sources will also be savvy to the risks they face, and might dictate their own safeguards in the reporter-source relationship. This could mean not using email, turning off a phone tracker, avoiding phone contact altogether or employing encryption technology. It could also mean meeting face-to-face or exchanging only hard-copy paper materials. It may also require an understanding of the relationship and the meaning of on-the-record or off-the-record.

For reporters who regularly deal with these weighty topics, this is the normal operation. But for reporters not accustomed to this, it requires an understanding of the concerns and risks.

The Government Accountability Project’s guide, Working with Whistleblowers, offers practical advice for reporters and whistleblowers alike. The relationship between the two is based on “trust, trust, trust.” GAP advises reporters to fully understand the risks their sources take and to honor their commitments.

GAP says: “Journalists who work with intelligence whistleblowers should realize that any story based on classified information may result in the whistleblower’s prosecution. The chances of reprisal are high, and even the most proficiently anonymous whistleblowers often can be traced based on work access or job duties.”

Roy S. Gutterman is an associate professor and director of the Tully Center for Free Speech at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University.

Next: Technology Can Help Whistleblowers Communicate Anonymously